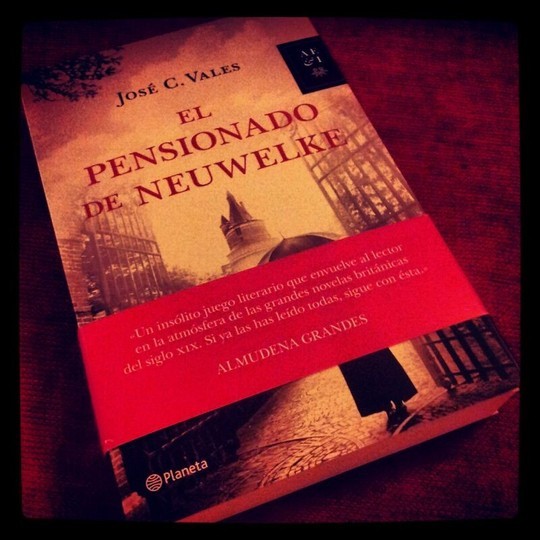

El Pensionado de Neuwelke

"En nuestro tiempo de realismos y descreimientos, apenas se atreve uno a declarar que el mundo es un lugar asombroso, lleno de misterios y maravillas incomprensibles; sin embargo y por fortuna, el mundo no es tan simple y tan vulgar como creen quienes son incapaces de asombrarse ante el agua, una manzana o una luciérnaga. Si los simplistas se permitieran un instante de reflexión, admirarían esos objetos con un asombro cercano al anonadamiento. Además, el mundo no sólo es maravilloso, enigmático y misterioso, sino que parece la mismísima imagen de una fertilidad desbocada, repleta y llena de miles y millones de objetos y seres, formando un caos que sólo la presunción y el envanecimiento pueden considerar sometido al imperio de la razón y la ciencia. Por fortuna más que por desgracia, nuestro universo es caótico, azaroso, incomprensible y sorprendente, y no admirarse ante el monumental desconcierto de la vida sólo revela una cierta incapacidad para gozar de ella.

La historia del Pensionado de Señorita de Neuwelke, en buena parte, es la historia del fabuloso caos del mundo y sus objetos, y de personas reales que tuvieron que vivir allí donde la confusión y el desconcierto de la existencia se revelaron de un modo maravilloso".

José C. Vales: El Pensionado de Neuwelke, Planeta, Barcelona, 2013; pág. 13.

El Pensionado de Neuwelke se concibió como un apasionado homenaje a la literatura del Romanticismo y narra la extraordinaria historia de una institutriz francesa durante su estancia en un remoto internado de señoritas en Livonia. Basada en la historia real y documentada de la maestra Émilie Sagée, la novela recrea la vida de esta joven, aquejada de una rara y terrible afección que la convierte en una proscrita. Tras recorrer Europa huyendo de un implacable exorcista, la institutriz llega al Pensionado de Señoritas de Neuwelke, en los gélidos y desolados parajes bálticos. En el internado, por fin, Émilie cree haber encontrado el sosiego y la paz que anhelaba: el propietario del colegio, los profesores, las damas de compañía y las alumnas, junto a un viejo y malhumorado jardinero escocés, conforman un paisaje humano en el que la amistad, la generosidad y la honradez se verán forzadas a luchar contra los celos, las ambiciones y el fanatismo.

El caos, las sonrisas y la muerte

Dossier de prensa · Extractos

Desde la introducción del narrador (un embajador de la reina Victoria en la Europa oriental) parece evidente que la propuesta del autor es mostrar hasta qué punto la existencia puede entenderse como un compendio maravilloso y aterrador de circunstancias sobre las que el individuo no tiene ningún poder. “Nuestro universo es caótico”, dice el narrador en las primeras páginas, “azaroso, incomprensible y sorprendente, y no admirarse ante el monumental desconcierto de la vida sólo revela una cierta incapacidad para gozar de ella”. Los personajes de la novela, y muy especialmente Émilie, se sienten aterrados ante un mundo atestado de circunstancias sobre las que no tienen influencia alguna. Émilie, como la señorita Eveline y otros personajes, no son más que víctimas de un mundo incomprensible y caótico. “Todo lo que podía explicar razonablemente era que la vida le parecía un acontecimiento desconcertante y misterioso, tan hermoso como aterrador, tan lógico como ridículo; la vida le resultaba ingobernable, y los hombres y mujeres que deambulaban por la existencia se parecían demasiado a pequeños barcos perdidos en el océano...”. Y añade más adelante: “La vida le parecía un milagro asombroso, una formidable casualidad, una sorpresa irremediable y peligrosa”.

Sin embargo, y por fortuna para el lector, El Pensionado de Neuwelke no es una excusa para un fárrago filosófico. Se trata sencillamente de una buena historia contada del mejor modo posible. Los lectores han apreciado especialmente el sentido del humor del narrador, que con frecuencia se inclina hacia la ironía o el sarcasmo, a las burlas sociales y las chanzas sobre caracteres. En este punto parece seguir de cerca el humor dickensiano, y también el de Trollope o Austen o Collins. Curiosamente, es el humor –en una historia dramática– lo que aporta la dosis de verosimilitud que precisa una buena historia. Los lectores que frecuenten la novelística británica decimonónica encontrarán lugares en los que divertirse enormemente.

Aunque es probable que El Pensionado de Neuwelke acabe resumiéndose como la extraña y misteriosa historia de una maestra del siglo XIX en un remoto paraje báltico, los lectores seguramente cerrarán el libro con una impresión bien distinta. Desde luego, es cierto que el armazón argumental es la sucesión de apariciones espectrales que acontecieron en el Pensionado de Neuwelke –aquí oportunamente modificadas frente al relato de Owen, para dar forma a una narración moderna–, pero la novela se esfuerza sobre todo en las relaciones humanas, en la generosidad y la fidelidad de la amistad, en la solidaridad frente a la desgracia, y en el valor de la honradez y la justicia frente a la mezquindad.

De "Imágenes e imaginación romántica", de David T. Gies

Para los que participaban en la vida intelectual de la época, la literatura romántica articulaba gran número de ideas perturbadoras y presentaba una plétora de fascinantes imágenes poéticas. No existía ningún plan ideológico coherente en el movimiento romántico, ni podemos discernir ningún bien pensado programa de cambio social: las diferentes, y a veces contradictorias ideas estéticas, filosóficas y políticas que dominaron la primera mitad del siglo XIX aseguraban esta brillante incoherencia. [...]

Todos conocemos los repetidos topoi del Romanticismo. Los escritores [románticos] no inventaron las imágenes que usaron para expresar sus temas, pero es importante notar que todas las obras que se consideran románticas muestran una sorprendente conformidad en la repetición de ciertas imágenes [...], imágenes que se apoyan en cuatro temas centrales. Éstos son, a mi modo de ver, el tema de la Enajenación, el tema de la Fatalidad, el tema de la Confrontación y el tema del Rechazo.

Enajenación. El héroe romántico se cree -y está- aislado de la sociedad. Con frecuencia se encuentra solo y separado de la cómoda protección del statu quo. Tal marginalidad se expresa literariamente en los orígenes del héroe, la ira y la hostilidad que le dirigen los representantes del poder y de la autoridad y el aire de misterio que inevitablemente oscurece su verdadera identidad. En otro plano, la manifestación de esta separación se expresa a través de imágenes que representan la enajenación física: el héroe se encuentra escondido detrás de varias máscaras o encarcelado en una prisión, un monasterio, una cueva o hasta una mansión infernal cuyas puertas se abren hacia un plano de maldición eterna.

Fatalidad. Fatalidad, mala suerte, estrella negra, fortuna adversa, destino, sino, azar: todos estos elementos se expresan en una espesa red de imágenes que domina el universo romántico. La Weltanschauung romántica exigía un héroe oprimido por la adversa suerte, condenado a la ira divina sin esperanza de escape o salvación.

Confrontación. Un sentido de confrontación penetra estas obras [románticas]. La rebelión y el desafío se expresan no sólo en la actitud personal del héroe contra la tiranía emocional y social que siente sino también en su actitud política. La combinación de su actitud interior con sus acciones se hará patente más tarde en un plano aún más amplio, el plano cósmico. Lo primero que tiene que hacer el héroe romántico es luchar contra las restricciones emocionales planteadas por su propia familia o la de su amante. [...] El héroe se encuentra con la necesidad de romper esas barreras; se resuelve a derribar las murallas de oposición, y la rebelión que esto representa se exterioriza en su lucha contra poderes políticos.

Rechazo. Las imágenes que aparecen alrededor del tema del Rechazo son numerosas, y se ven más claramente en las numerosas comparaciones dialécticas que forman el eje central del vocabulario romántico: vida/muerte, amor/odio, luz/oscuridad, ángel/diablo, Dios/Satanás, cielo/infierno, salvación/condenación, etcétera. La continua vacilación entre estos elementos resulta de un desequilibrio emocional y deja ese residuo de desesperación ontológica que todos reconocemos en el héroe romántico.

* * *

El Romanticismo era un cataclismo revolucionario tanto social como moral, literario y político, que, cuando tuvo éxito, transformó al hombre en un ser radicalmente nuevo.

De "Imágenes y la imaginación románticas", de David T. Gies, incluido en VV. AA.: El romanticismo, Ed. D. T. Gies, Taurus, Madrid, 1989; págs. 140-151.

El Pensionado de Neuwelke es la historia de una joven institutriz francesa aquejada de una rara y terrible afección que la convierte en una proscrita. Tras recorrer Europa huyendo de un implacable exorcista, la maestra llega al Pensionado de Señoritas de Neuwelke, en los gélidos y desolados parajes de Livonia. Allí, por fin, Émilie cree haber encontrado el sosiego y la paz que anhelaba: el propietario del colegio, los profesores, las damas de compañía y las alumnas, junto a un viejo y malhumorado jardinero escocés, conforman un paisaje humano en el que la amistad, la generosidad y la honradez se verán forzadas a luchar contra los celos, las ambiciones y el fanatismo.

El origen de la historia

La referencia básica de la historia narrada en El Pensionado de Neuwelke es una anécdota que aparece en el libro Footfalls of the Boundary of Another World, with Narrative Illustrations, de Robert Dale Owen, antiguo miembro del Congreso [de los Estados Unidos] y comisionado americano en Nápoles. El ejemplar utilizado se publicó en Philadelphia, en la editorial de J. B. Lippincott y Co., en 1860. De algunas informaciones marginales se deduce que se reeditó posteriormente en 1869, y en otras ocasiones, con algunas modificaciones. Esta obra reúne los numerosísimos ejemplos que su autor, aficionado a los sucesos paranormales, pudo recopilar sobre este tema, ofreciendo explicaciones y teorías al respecto.

A continuación se transcriben las páginas 348-357 (Book IV, "Of Appearances Commonly Called Apparitions", Chap. III) de la obra citada, fuente y base de la novela El Pensionado de Neuwelke.

WHY A LIVONIAN SCHOOL-TEACHER LOST HER SITUATION.

Habitual Apparition of a Living Person.

[348] There existed in the year 1845, and still continued, in Livonia, about thirty-six miles from Riga and a mile and half from the small town of Wolmar, an institution of high repute for the education of young ladies, entitled the Pensionnat of Neuwelcke. It is under the superintendence of Moravian directors; of whom the principal, at the times of the occurrences about to be related, was named Buch.

There were, in that year, forty-two young ladies residing there as boarders, chiefly daughters of noble Livonian families; among them, Mademoiselle Julie, second daughter of the Baron de Guldenstubbé, then thirteen years of age.

[349] In this institution one of the female teachers at that time was Mademoiselle Emélie Sagée, a French lady, from Dijon. She was of the Northern type, —a blonde, with very fair complexion, light-blue eyes, chestnut hair, slightly above the middle size, and of slender figure. In character she was amiable, quiet, and good tempered; not at all given to anger or impatience; but of an anxious disposition, and as to her physical temperament, somewhat nervously excitable. Her health was usually good; and during the year and a half that she lived as teacher at Neuwelcke she had but one or two slight indispositions. She was intelligent and accomplished; and the directors, during the entire period of her stay, were perfectly satisfied with her conduct, her industry, and her acquirements. She was at that time thirty-two years of age.

A few weeks after Mademoiselle Sagée first arrived, singular reports began to circulate among the pupils. When some casual inquiry happened to be made as to where she was, one young lady would reply that she had been seen her in such or such a room; whereupon another would say: “Oh, no! She can’t be there; for I have just met her on the stairway”; or perhaps in some distant corridor. At first they naturally supposed it was mere mistake; but, as the same thing recurred finally spoke to the other governesses about it. Whether the teachers, at that time, could have furnished an explanation or not, they gave none: they merely told the young ladies it was all fancy and nonsense, and bade them pay no attention to it.

But, after a time, things much more extraordinary, and which could not be set down to imagination or mistake, began to occur. One day the governess was giving a lesson to a class of thirteen, of whom Mademoiselle de Guldenstubbé was one, and was demonstrating, with [350] eagerness, some proposition, to illustrate which she had occasion to write with chalk on a blackboard. While she was doing so, and the young ladies were looking at her, to their consternation, they suddenly saw two Mademoiselle Sagées, the one by side of the other. They were exactly alike; and they used the same gestures, only that the real person held a bit of chalk in her hand, and did actually write, while the double had no chalk, and only imitated the motion.

This incident naturally caused a great sensation in the establishment. It was ascertained, on inquiry, that every one of the thirteen young ladies in the class had seen the second figure, and that they all agreed in their description of its appearance and of its motions.

Soon after, one of the pupils, a Mademoiselle Antonie de Wrangel, having obtained permission, with some others, to attend a fête champêtre in the neighborhood, and being engaged in completing her toilet, Mademoiselle Sagée had good-naturedly volunteered her aid, and was hooking her dress behind. The young lady, happening to turn round and look in a adjacent mirror, perceived two Mademoiselle Sagées hooking her dress. The sudden apparition produced so much effect upon her that she fainted.

Months passed by, and similar phenomena were still repeated. Sometimes, at dinner, the double appeared standing behind the teacher’s chair and imitating her motions as she ate, —only that its hands held no knife and fork, and that there was no appearance of food; the figure alone was repeated. All the pupils and the servants waiting on the table witnessed this.

It was only occasionally, however, that he double appeared to imitate the motions of the real person. Sometimes, when the latter rose from a chair, the figure would appear seated on it. On one occasion, Mademoiselle Sagée being confined to bed with an attack of [351] influenza, the young lady alreade mentioned, Mademoiselle de Wrangel, was sitting by her bedside, reading to her. Suddenly the governess became stiff and pale; and, seeming as if about to faint, the young lady, alarmed, asked if she was worse. She replied that she was not, but in a very feeble and languid voice. A few seconds afterward, Mademoiselle de Wrangel, happening to look round, saw, quite distinctly, the figure of the governess walking up and down the apartment. This time the young lady had sufficient self-control to remain quiet, and even to make no remark to the patient. Soon afterward she came down-stairs, looking very pale, and related what she had witnessed.

But the most remarkable example of this seeming independent action of the two figures happened in this wise.

One day all the young ladies of the institution, to the number of forty-two, were assembled in the same room, engaged in embroidery. It was a spacious hall on the first floor of the principal building, and had four large windows, or rather glass doors, (for they opened to the floor), giving entrance to a garden of some extent in front of the house. There was a long table in the center of the room; and here it was that the various classes were wont to unite for needle-work or similar ocupation.

On this occasion the young ladies were all seated at the table in question, whence they could readily see what passed in the garden; and, while engaged at their work, they had noticed Mademoiselle Sagée there, not far from the house, gathering flowers, of which she was very fond. At the head of the table, seated in an arm-chair, (of green morocco, my informant says, she still distinctly recollects that it was), sat another teacher, in charge of the pupils. After a time this lady had occasion to leave the room, and the arm-chair was left vacant. It remained so, however, for a short time only; for of a [352] sudden there appeared seated in it the figure of Mademoiselle Sagée. The young ladies inmediately looked into the garden, and there she still was, engaged as before; only they remarked that she moved very slowly and languidly, as a drowsy or exhausted person might. Again they looked at the arm chair, and there she sat, silent, and without motion, but to sight so palpably real that, had they not seen her outside in the garden and had they not known that she appeared in the chair without having walked into the room, they would all have supposed that it was the lady herself. As it was being quite certain that it was not a real person, and having become, to a certain extent, familiar with this strange phenomenon, two of the boldest approached and tried to touch the figure. They averred that they did feel a slight resistance, which they likened to that which a fabric of fine muslin or crape would offer to the touch. One of the two then passed close in front of the armchair, and actually through a portion of the figure. The appearance, however, remained, after she had done so, for some time longer, still seated, as before. At last it gradually disappeared; and then it was observed that Mademoiselle Sagée resumed, with all her usual activity, her task of flower-gathering. Every one of the forty-two pupils saw the same figure in the same way.

Some of the young ladies afterward asked Mademoiselle Sagée if there was any thing peculiar in ther feelings on this occasion. She replied that she recollected this only: that, happening to look up, and perceiving the teacher’s arm-chair to be vacant, she had thought to herself, “I wish she had not gone away: these girls will be sure to be idling their time and getting into some mischief”.

This phenomenon continued, under various modifications, throughout the whole time that Mademoiselle Sagée retained her situation at Neuwelcke; that is, [353] throughout a portion of the years 1845 and 1846; and, in all, for about a year and a half; at intervals, however, —sometimes intermitting for a week, sometimes for several weeks at a time. It seemed chiefly to present itself on occasions when the lady was very earnest or eager in what she was about. It was uniformly remarked that the more distinct and material to the sight the double was, the more stiff and languid was the living person; and in proportion as the double faded did the real individual resume her powers.

She herself, however, was totally unconscious of the phenomenon: she had first become aware of it only from the report of others; and she usually detected it by the looks of the persons present. She never, herself, saw the appearance, nor seemed to notice the species of rigid apathy which crept over her at the times it was seen by others.

During the eighteen months throughout which muy informant had an opportunity of witnessing this phenomenon and of hearing of it through others, no example came to her knowledge of the appearance of the figure at any considerable distance —as of several miles— from the real person. Sometimes it appeared, but not far off, during their walks in the neighborhood; more frequently, however, within-doors. Every servant in the house had seen it. It was, apparently, perceptibly to all persons, without distinction of age or sex.

It will be readily supposed that so extraordinary a phenomenon could not continue to show itself, for more than a year, in such an institution, whitout injury to its prosperity. In point of fact, as soon as it was completely proved, by the double appearance of Mademoiselle Sagée before the class, and afterward before the whole school, that here was no imagination in the case, the matter began to reach the ears of the parents. Some of the more timid among the girls, also, became much excited, and evinced great alarm whenever they hap[354]pened to witness so strange and inexplicable a thing. The natural result was that their parents began to scruple about leaving them under such a influence. One after another, as they went home for the holidays, failed to return; and though the true reason was not assigned to the directors, they knew it well. Being strictly upright and conscientious men, however, and very unwilling that a well-conducted, diligent, and competent teacher should lose her position on account of a peculiarity that was entirely beyond her control —a misfortune, not a fault—they persevered in retaining her, until, at the end of eighteen months, the number of pupils had decreased from forty-two to twelve. It then became apparent that either the teacher or the institution must be sacrificed; and, with much reluctance and many expression of regret of the part of those to whom her amiable qualities had endeared her, Mademoiselle Sagée was dismissed.

The poor girl was in despair. “Ah!” (Mademoiselle de Guldenstubbé heard her exclaim, soon after the decision reached her), “Ah! the nineteenth time! It is very, very hard to bear!”. When asked what she meant by such an exclamation, she reluctantly confessed that previous to her engagement at Neuwelcke she had been teacher in eighteen different schools, having entered the first when only sixteen years of age, and that, on account of the strange and alarming phenomenon which attached to her, she had lost, after a comparatively brief sojourn, one situation after another. As, however, her employers were in every other respect well satisfied with her, she obtained in each case favorable testimonials as to her conduct and abilities. Dependent enterely on her labor for support, the poor girl had been compelled to avail herself of these in search of a livelihood, in places where the cause of her dismissal was not known; even though she felt assured, from expe [355] rience, that a few months could not fail again to disclose it.

After she left Neuwelcke, she went to live, for a time, in the neighborhood, with a sister-in-law, who had serveral quite young children. Thither the peculiarity pursued her. Mademoiselle de Guldenstubbé, going to see her there, learned that the children of three or four years of age all knew of it; being in the habit of saying that “they say two Aunt Emélies”.

Subsequently she set out for the interior of Russia, and Mademoiselle de Guldenstubbé lost sight of her entirely.

That lady was not able to inform me whether the phenomenon had shown itself during Mademoiselle Sagée’s infance, or previous to her sixteenth year, nor whether, in the case of her family or of her ancestors, a similar peculiarity had appeared.

I had the above narrative from Mademoiselle de Guldenstubbé herself; and she kindly gave me permission to publish it, with every particular of name, place, and date. She remained as pupil at Neuwelcke during the whole time that Mademoiselle Sagée was teacher there. No one, therefoore, could have had a better opportunity of observing the case in all its details.

In the course of my reading on this subject —and it has been somewhat extensive— I have not met with a single example of the apparition of the living so remarkable and so incontrovertibly authentic as this. The institution of Neuwelcke still exists, having gradually recovered its standing after Mademoiselle Sagée left it; and corroborative evidence can readily be obtained by addressing its directors.

The narrative proves, beyond doubt or denial, that, under particular circumstances, the apparition of counterpart of a living person may appear at a certain distance from that person, and may seem, to ordinary [356] human sight, so material as not to be distinguishable from a real body; also that this appearance may be reflected from a mirror. Unless the young ladies who were courageous enough to try the experiment of touching it were deceived by their imaginations, it proves, further, that such an aparition may have a slight, but positive, consistency.

It seems to prove, also, that care or anxiety on the part of the living person may project (if I may so express it) the apparition to a particular spot. Yet it was sometimes visible when no such cause could be assigned.

It proves, further, that when the apparition separated (if that be the correct expression) from the natural body, it took with it a certain portion of that body’s ordinary life and strength. It does not appear that in this case the languor consequent upon such separation ever reached the state of trance or coma, or that the rigidity observed at the same time went as far as catalepsy; yet it is evident that the tendency was toward both of these conditions, and that that tendency was the greater in proportion as the apparition became more distinct.

Two remarkable peculiarities mark this case: one, that the appearance, visible without exception to every one else, remainded invisible to the subject of it; the other, that though the second figure was sometimes seen to imitate, like an image reflected in a mirror, the gestures and actions of the first, yet at other times it seemed to act entirely independent of it; appearing to walk up and down while the actual person lay in bed, and to be seated in the house while its counterpart moved about in the garden.

It differs from other cases on record in this: that the apparition does not appear to have shown itself at any considerable distance from the real person. It is possible (but this is theory only) that, if it had, the result on [357] Mademoiselle Sagée might have been to produce a state of trance during its continuance.

This case may afford us, also, a useful lesson. It may teach us that it is idle, in each particular instance of apparition or other rare and unexplained phenomenon, to deny its reality until we can discover the purpose of its appearance; to reject, in short, every extraordinary fact until it shall have been clearly explained to us for what great object God ordains or permits it. In this particular case, what special intention can be assigned? A meritorious young woman is, after repeated efforts, deprived by an habitual apparition of the opportunity to earn an honest livelihood. No other effect is apparent, unless we are to suppose that it was intended to warn the young girls who witnessed the appearance against materialism. But it is probable the effect upon them was to produce alarm rather than conviction.

The phenomenon is one of a class. There is good reason, doubtless, for the existenceo fo that class; but we ought not to be called upon to show the particular end to be effected by each example. As a general proposition, we believe in the great utility of thunder-storms, as tending to purify the atmosphere; but who has a right to require that we disclose the design of Providence if, during the elemental war, Amelia be stricken down a corpse from the arms of Celadon?

Referencias directas

Shelley, P. B.: Selected Poems, Random House, New York, 1994; “To —” // Shelley, M.: Frankenstein, trad. Vales, J. C., Espasa, Madrid, 2011) // Young, E.: Night Thoughts, Sharpe, London, 1827; Thomas Gray, Elegy Written in a Country Church-Yard, Bell, British Library, London, 1788; Ossian-MacPherson, BAE, Madrid, 1880 // Goethe, J. W., Las desventuras del joven Werther, Cátedra, Madrid, 1994, y Alba, Madrid, 2011. // Shakespeare, W.: Teatro selecto, Espasa Clásicos, Madrid, 2010 // Austen, J.: Orgullo y prejuicio, Emma, Mansfield Park, Juicio y sentimiento, etc., en Cátedra, Alba, Espasa et al. También obras completas en CRW, London, 2003, con ilustraciones de H. Thomson. // Rousseau, J. J.: Confesiones, Tebas, Madrid, 1978; y Les rêveries... Grenier, Gallimard, Saint Amand, 1972 // Schiller, F. von, Don Carlos, Guillermo Tell, Planeta, Barcelona, 1990 // Poetas románticos franceses, Lamartine, Vigny, V. Hugo, Nerval, Musset, Gautier, Planeta, Barcelona, 1990; Scott, W., Ivanhoe, Wordsworth Classics, Ware, 1995; y en esp. Planeta, Barcelona, 1991; //Poetas románticos ingleses, Byron, Shelley, Keats, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Planeta, Barcelona, 1996; // Blake, W.: Canciones de inocencia y esperanza, Cátedra, Madrid, 1995. // Byron, Selected Poems, Gramercy, New York, 1994. // Burns, Robert, The Works, Wordsworth, Ware, 1994. // Corneille-Racine, Teatro, Círculo, Barcelona, 1996 // Gay, J. Poetical Works, Apollo Press, Edimburg, 1784; Hazard, Paul, El pensamiento europeo en el siglo XVIII, Alianza, Madrid, 1991. // Hervey, T. Los sepulcros, Sanz, Madrid, 1830. // Richardson, S.: Clara Harlowe, Fuentenebro & al., Madrid, 1829; y Pamela Andrews, Imp. Real, Madrid, 1799. // Saint-Pierre, Bernardin, Pablo y Virginia, Cátedra, Madrid, 1989 // Volney, C. F. Chasseboeuf, Las ruinas de Palmira, Musa, L'Hospitalet, 1987. // Enciclopedia del saber antiguo y prohibido, Alianza, Madrid, 1987 // Bryson, B. En casa. Una breve historia de la vida privada, RBA, Barcelona, 2011; Tubau, Daniel: La verdadera historia de las sociedades secretas, Alba, Madrid, 2008. // J. J. Rousseau, J. W. Goethe, F. R. de Chateaubriand, M. Shelley, V. Hugo et al. Perspectivas del Mont Blanc, Alba, 2008 // Shermer, M. Por qué creemos en cosas raras, Pseudociencia, superstición y otras confusiones de nuestro tiempo, Alba, Madrid, 2008 // Fortea, J. A. Summa Daemoniaca, Palmyra, Madrid, 2008 // Fritze, Ronald H. Conocimiento inventado. Falacias históricas, ciencia amañada y pseudo-religiones, Turner, Madrid, 2010 // Baillargeon, N., Curso de autodefensa intelectual, Ares y Mares, Crítica, Barcelona, 2007 // Withington, J., Historia mundial de los desastres. Crónicas de guerras, terremotos, inundaciones y epidemias. Turner, Madrid, 2008. // Green, P. History of Nursery Rhymes, 1899. // “Vive la rose et le lilas”, canción popular francesa del siglo XVIII // Epístola ad Pisones de Horacio, CSIC, Madrid, 1982 // Hugo, V., Nuestra Señora de París, Cátedra, Madrid, 1985 // Chateaubriand, René – Atala, Cátedra, Madrid, 1989, // y Wordsworth – Coleridge, Baladas líricas, Cátedra, Madrid, 1990 // Lewis, M. G. El monje, Valdemar, Madrid, 1994, plus Vernon Lee, Oliphant, Edwards, y otros escritores góticos, esp. Sue, E. // Porter, Ray, Historia social de la locura, Crítica, Barcelona, 1989 // Laver J. Breve historia del traje y la moda, Arte Cátedra, Madrid, 2006 // Cosgrave, B., Historia de la moda, Gili, Barcelona, 2005 // Vales, José C. La revolución de la moda, Espasa, ed. no venal, Madrid, 2008. // Callejo, J. Hadas, Guía de los seres mágicos de España, Edaf, Madrid, 1995; Textos herméticos, Gredos, Madrid, 1999 //

Se han omitido aquí todos los estudios teóricos sobre historia, literatura, filosofía y estética del romanticismo, así como distintas obras de referencia sobre mitología clásica y nórdica, sobre jardinería y botánica, sobre historia de Inglaterra y textos bíblicos.